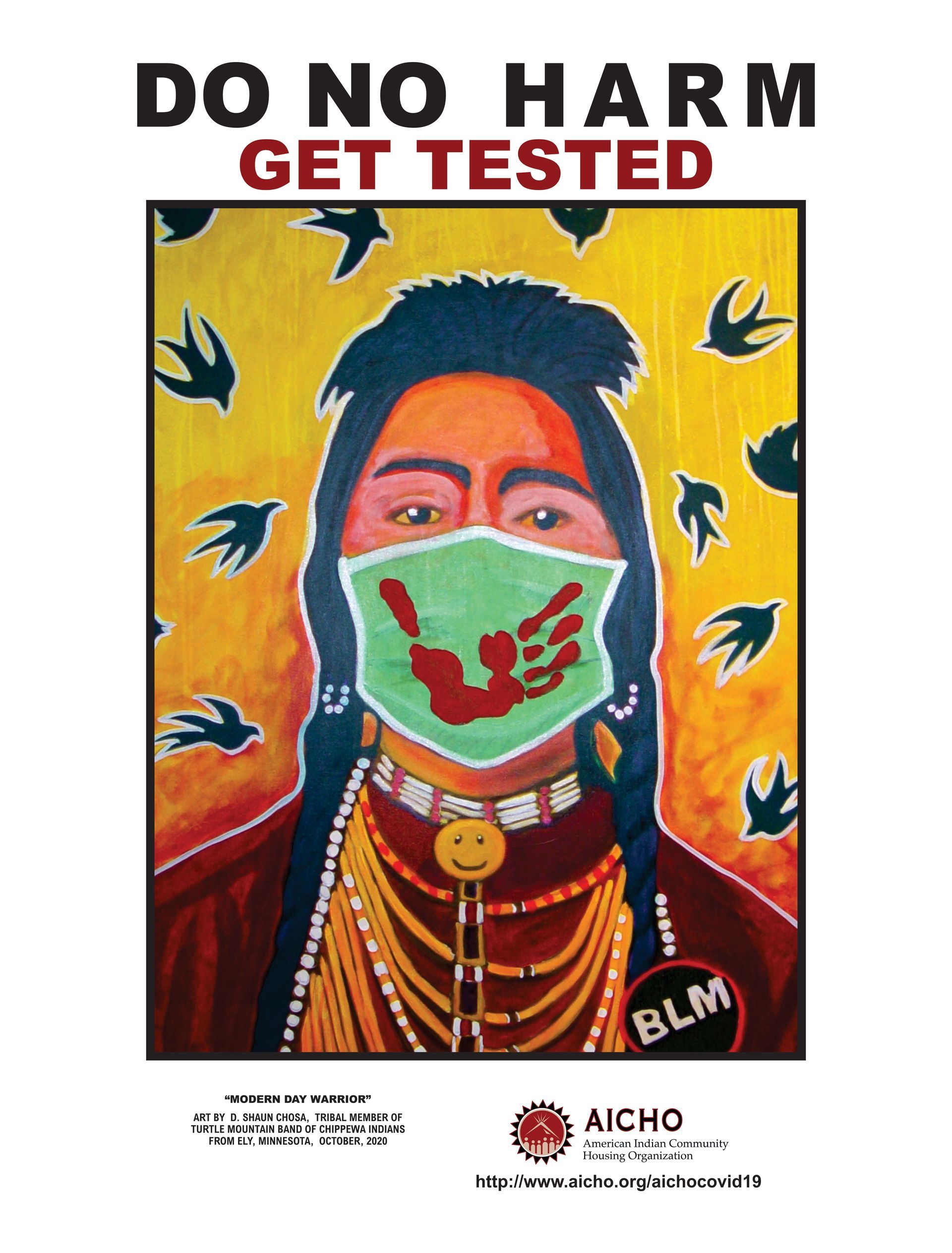

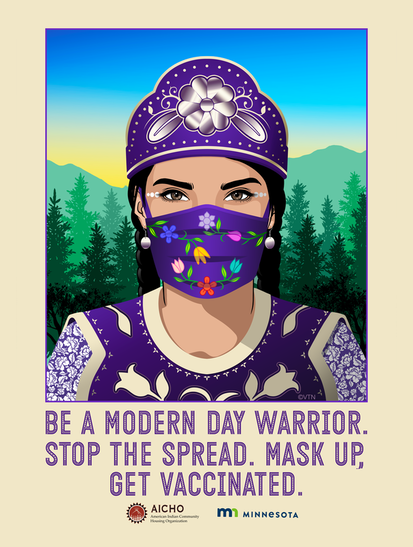

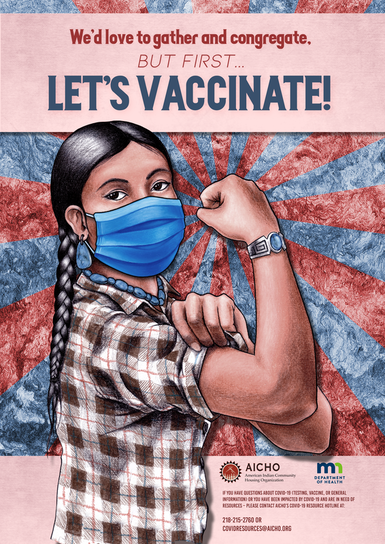

Nationally, a Native publishing company Native Realities, who focus on media that shines a powerful light through the Indigenous community lens, started to offer COVID posters online, which were shared in rapid style via social media. Building from this example, the Minnesota group started to brainstorm collaborative efforts with Indigenous artists. AICHO produced a series of electronic posters, later made into print posters and stickers, that featured images that resonated with Native communities conveying COVID prevention practices (creative responses to trauma). From powerful images of jingle dress dancers (a traditional dance delivered to the Ojibwe people by a dream to offer healing to individuals and the community), to the traditional mask of water protectors symbolizing resistance to environmental harm and viruses - different issues but equal threats, to the importance of elders and children and the need to value and protect them, these public health messages were received with excitement from the Indigenous and wider community. AICHO later expanded this kind of cultural messaging to t-shirts, hoodies (building collective public messages on being fully vaccinated), first aid kits, PPE, and other give-away items. It was the first time we witnessed Native communities taking ample copies of public health information, for themselves and to share “at the office, in the community center, at the Boys & Girls Club, at my sister’s, at my Mom’s” (collective action- community participation in arts activities leading to deeper engagement). AICHO provided regional distribution, driving to outdoor social gatherings and Tribal community centers. We intentionally went to remote communities who are often the most under-resourced and left out communities (civic engagement- initiating desire for hyper-local civic engagement, high opportunity, low barrier).

AMERICAN INDIAN COMMUNITY HOUSING ORGANIZATION (AICHO)

DULUTH, MN

WE-Making is a suite of resources that explores the relationship between place-based arts practices and social cohesion to advance health equity and community wellbeing. This We-Making story demonstrates how place-based arts and cultural strategies uniquely contributed to social cohesion and wellbeing in this community. Throughout this story you’ll see terms paired with actions in parentheses (e.g., social capital, collective action, place attachment, civic engagement, self-determination of shared values). This denotes for the reader how the WE-Making framework was specifically incorporated. Explore the WE-Making framework and resources.

In early March 2020, the American Indian Community Housing Organization (AICHO) was planning a third Indigenous Winter Market, an indoor farmers and art market showcasing local Indigenous food producers and artists. Another event, Here Comes the Sun, was planned on the same date at the Gimaajii Building to feature a Native-owned solar installation company, Solar Bear, and hands-on activities for youth and community members to learn about renewable energy. An AICHO team member had just returned from St. Paul from a rally day at the State Capitol on housing issues and relayed to the full AICHO team that many places in the metro area were preparing to close, people were stocking up on food and household items, and the energy felt different than anything she had ever experienced before. These were the first days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our team realized this was not an idle threat but was larger than anything we had gone through before. This was the day AICHO went into mobilization. We canceled our community events and went into crisis response and planning mode.

AICHO is an Indigenous-focused organization in a small urban community of Duluth, Minnesota on the western tip of Lake Superior. Known as the “Great Sea” region in traditional Anishinaabe language, the area has been the homelands of the Ojibwe/Anishinaabe, Dakota, Northern Cheyenne, and other Tribal Nations. In 1854, the United States government made a treaty with the Ojibwe people, to cede much of the territory, establish reserved areas of land for Tribal Nations, and prepare the different territories for statehood. Duluth, a long-standing trade area and home to traditional villages, became a new hub for shipping out raw materials of timber and iron ore. After almost two centuries of federal policies directed at disrupting Indigenous community and culture, the Indigenous community persists in resistance to assimilation and cultural and community demise. Duluth continues to be the homelands for many Indigenous people, from numerous Tribal Nations, who have maintained a steady community in a city that is now predominantly white. As a non-profit formed in 1993, AICHO responds to both challenges that threaten and opportunities that advance Indigenous resilience.

After three decades of community work, AICHO was fueled by a strong mission to honor resiliency and put a series of cultural strategies in motion, leaning into community strengths. AICHO had nurtured strong relationships with grassroots leaders (social capital- bridging), built a staff team who shared the direct life experiences of Native and BIPOC existence and surviving with limited or no resources (civic engagement; self determination of shared values), and steadily expanded long-standing partnerships with regional Tribal Nations (social capital- bridging). In 2012, AICHO opened the Gimaajii-Mino-Bimaadizimin (We Are, All of Us, Beginning a Good Life Together) Building, which offers 29 units of permanent supportive housing, a community cultural center, a gym, office space for other Tribal organizations, and an ambitious plan for social enterprise, including the Indigenous First Art Gallery and Gift Shop, acquiring a print production company, and a corner grocery store. AICHO was actively developing the Niiwin Indigenous Food Market, a new Indigenous Arts Center, and an affordable housing development in partnership with a national developer . AICHO was also known for hosting large, vibrant cultural events that brought the community together in Duluth and from across the region. These events have always been in partnership with Indigenous artists and traditional knowledge holders, embedding art and culture in everything AICHO does (celebration and preservation of culture).

Pandemics are seared in Indigenous DNA ancestral memory. At AICHO, we felt the past reverberate through us and this gave us an extra sense of urgency as we prepared to mobilize.

The AICHO team gathered the most up to date health information, learning as much as we could immediately about COVID-19, who was at highest risk, modes of transmission, and recommended best practices for prevention. AICHO thought through what a “stay in place” order would possibly look like and how it would impact households with limited resources. AICHO created emergency food boxes, waived the next month’s rent for all AICHO housing households, closed all public spaces and canceled all events, and upped our cleaning game. At this time, the Governor’s office started to have direct dialogue sessions with urban American Indian organizations, Tribal Nations, and other culturally-specific groups across Minnesota to relay updated health information and hear from communities. AICHO joined a weekly meeting with the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) and other Indigenous leaders. In this space, we shared our strategies and started to build a response together (collective action).

AICHO then mobilized to secure new resources to meet the new challenges facing our community. AICHO secured funding to set up a community food distribution, something we had never done before or even imagined doing. In two weeks of receiving the funds, AICHO purchased food inventory, storage equipment, a data tracking system, PPE supplies, and refrigerators and freezers to launch bi-weekly curbside food distribution for all community members (low barrier; creative responses to trauma). We named the food distribution “Giwiidookodaadimin”, meaning “we help each other”, to signify during a collective crisis, we all work to help one another, whether it’s by simply putting a face mask on, staying in place for a period of time, figuring out resources, or supporting and sending love to one another. AICHO had a standing inventory of culturally-specific Indigenous foods and started to build stronger relationships with Indigenous food producers and local farmers across the immediate region. The emphasis for AICHO’s food distribution was fresh, organic, and high-quality foods. Indigenous chefs in the Twin Cities had started creating prepared meals for elders focused on using only traditional Indigenous ingredients. AICHO secured some of their frozen soups to distribute to area elders and started to create food packages specific to elders and to community members who were living without shelter. AICHO witnessed a dramatic rise of unsheltered Native community members during the pandemic, who often cooked over open fires or simply did not heat their food. The St. Paul Division of Indian Work shared with us strategies they used in putting together their food bags designed for people staying outdoors. All food distribution included PPE, household supplies, and cultural health messages.

The pandemic was a series of unknowns. At first, we didn’t know what the virus meant and the first response was focused on health information and prevention. The next response focused on access to testing and keeping others safe. Finally, once the COVID vaccinations became available, our response was to help to make the vaccines accessible. All of this happened in a national political climate that polarized health practices and caused mistrust. The AICHO team worked to bring vaccine clinics onsite and used our social media and community connections to get the word out. Once again, Indigenous artists came to the rescue. They pitched in with art pieces showing Native people with their sleeves rolled up, images of elders protecting children and wrapping them in traditional blankets with the words “fully vaccinated” etched in the edging declaring “Our Indigenous Future”, and a Native mom with her little ones, braiding her daughter’s hair with the message “Keep our Future Safe, Vaccinate.” AICHO worked with artists to send out messages on nurturing mental health, sexual health, and healthy eating (mindset- orientation toward common good).

In our community and nationwide, Indigenous people have been largely made invisible. We are often talked about in past tense, like we once existed but no longer are here. AICHO put our COVID response and cultural and art messages on social media, billboards, and in the regional news. We mobilized during the pandemic in a big way that would make our ancestors proud, carried forward by our cultural strength that has been tested by many historic crisis experiences and refined through these collective experiences to ensure “We Are Still Here”.

At AICHO, our mission is to honor the resilience of our people and we know we are “resilient because we are together”, which is our most important cultural teaching.